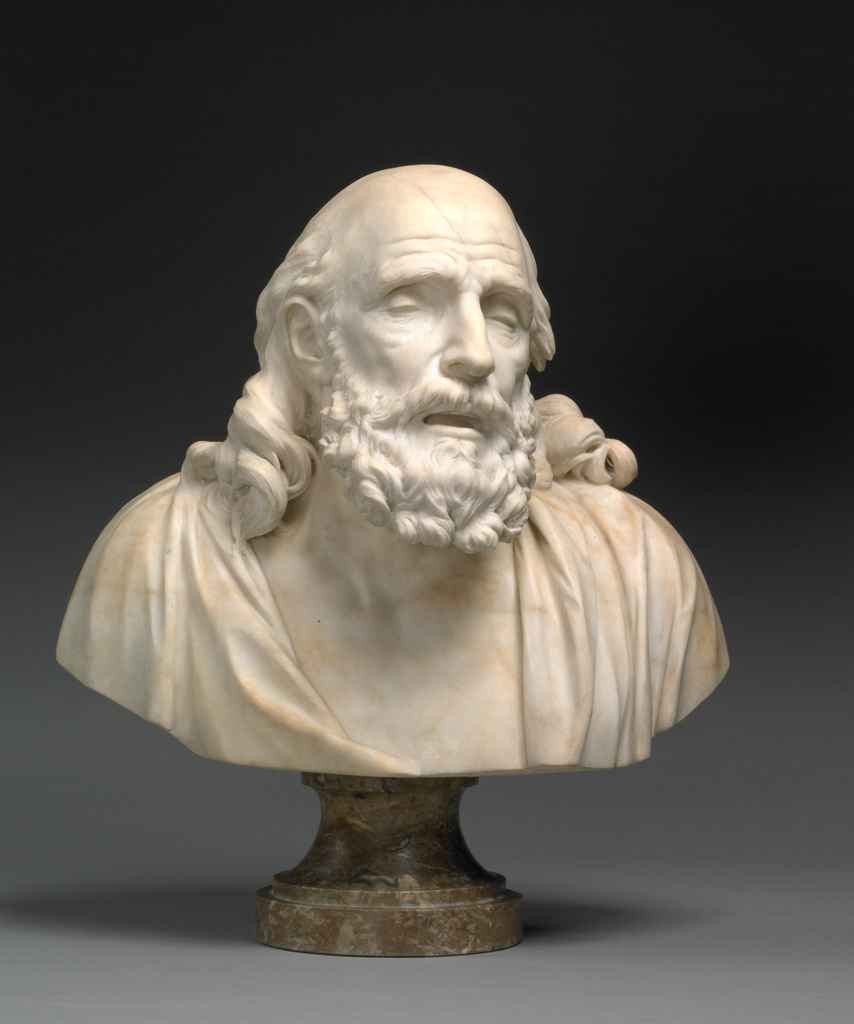

Museum description: This aged and emaciated figure is the blind general Belisarius. Heavy eyelids almost completely cover his eyes, which register nothing of the outside world. Deeply set eye sockets, encircled by wrinkles, also draw attention to Belisarius’s blindness. His veined and wrinkled forehead, tilted head, and open mouth, emphasize his vulnerable state. (More here.)

Boad: What moves me about his piece comes from knowing a little history of the great Roman general, Flavius Belisarius. As a long time loyal general, confidant, adviser and strategist for the Emperor Justinian, he had, through the course of time, become entangled in political intrigues which eventually rendered him an enemy to the Emperor, who as legend has it had his eyes put out as punishment. He was left to beg for his food during the remaining years of his life. What he did during that time is instructional. Saddled with a burden of guilt, which he felt came as a result of his sins and subsequent offense to God, he spent the remainder of his life begging, perhaps, but possibly not for food. More likely it was for the funds needed to build a church East of Trevi Fountain in Rome, and two hospices, through which he provided comfort for the sick and suffering.

As men, civilization teaches us to be strong and ambitious. Certainly, the great general reached the pinnacle of his career. But as is so often the case with greatness, it is precarious and ephemeral. Jean-Baptiste Stouf captures Belisarius just when he’s becoming interesting. When he has nothing left to lose. At that point he turns his heart and mind to God and his fellow man. No longer caught up in the callow pursuit of power, glory or money, our subject is blind, bald, scarred, wrinkled, old and alone. When there is nothing left to lose a common theme runs through the annals of history. Men turn to God. God, in turn, swift to forgive, uses men to provide relief, comfort, kindness and charity to humanity.

Our hero was not immortalized because he was a great general. We know his name today because he was a great general who became a great and humble man. Civilization does teach us to be strong and ambitious. Cheers to the fathers, the mentors and communities who teach men to be charitable.

Micah: